Burning Down the House Q&A

What is libertarianism, and why does it matter?

Libertarianism takes multiple forms. Libertarians once defended free markets, and the inequalities that markets inevitably generate, without claiming that those inequalities are deserved, or that people’s needs count for nothing. Free markets were valuable precisely because they offered the most promising path toward satisfying the needs of the worst off.

This valid core of libertarianism has prevailed across the political spectrum, so completely that the label “libertarian” is no longer meaningful as a way to describe it. What was valid in libertarianism has been assimilated into mainstream liberalism. Except for a politically impotent fringe, the American left aims for a generous welfare state – more generous than the present one – in the context of capitalism. The American right, too, has embraced the welfare state in some form. Few Republicans propose to abolish Medicare and Social Security.

Libertarianism is a mutated form of liberalism, the political philosophy that holds the purpose of government to be guaranteeing to individuals the freedom to live as they like. The distinctive claim of libertarians is that the best way to guarantee this freedom is to impose severe limits on government, barring much of the regulation and redistribution that today is routine. It is radical because it proposes to dismantle political institutions that are in fact now delivering freedom to millions. It is an infantile fantasy of godlike self-sufficiency. People in fact cannot be free in isolation. There can be no freedom without institutions. Structures of responsible regulation, and nonmarket transfers of income and wealth, are necessary preconditions of liberty.

The story of the corruption of libertarianism is a sad tale with a hopeful ending. It has pitted decent Americans against one another, the left suspecting the right of blind rapaciousness, the right suspecting the left of malicious envy. The encouraging news is that they are less far apart than they think. Libertarianism is most persuasive when it shares the commitments of the political left. The disagreement is not about ends. It concerns strategy. Too many on the left fail to grasp that the original libertarian strategy has been massively vindicated. The capacity of markets to alleviate poverty has been so overwhelmingly demonstrated in recent decades that it is silly to keep denying it. Too many on the right fail to grasp that unregulated markets cannot deliver a livable world. Therefore, moderate libertarianism can bridge some of the bitterest divisions of contemporary American politics.

Why is this book important to our current climate?

Growing numbers of Americans – a full third of those aged 18 to 29 – identify as libertarian. Libertarian ideas are powerfully influential in the Republican Party, which for decades has striven to cut taxes, reduce regulation, and limit assistance to the poor (notably the medical care supplied by Obamacare). One of the most powerful ideas in American politics is the belief that reducing the size and scope of government will make people freer.

Yet no book exists that examines libertarianism with anything other than uncritical enthusiasm. It is in fact, in its most common forms, a dangerous delusion. This book explains what libertarianism is, how it developed, and why it threatens the liberty it purports to protect.

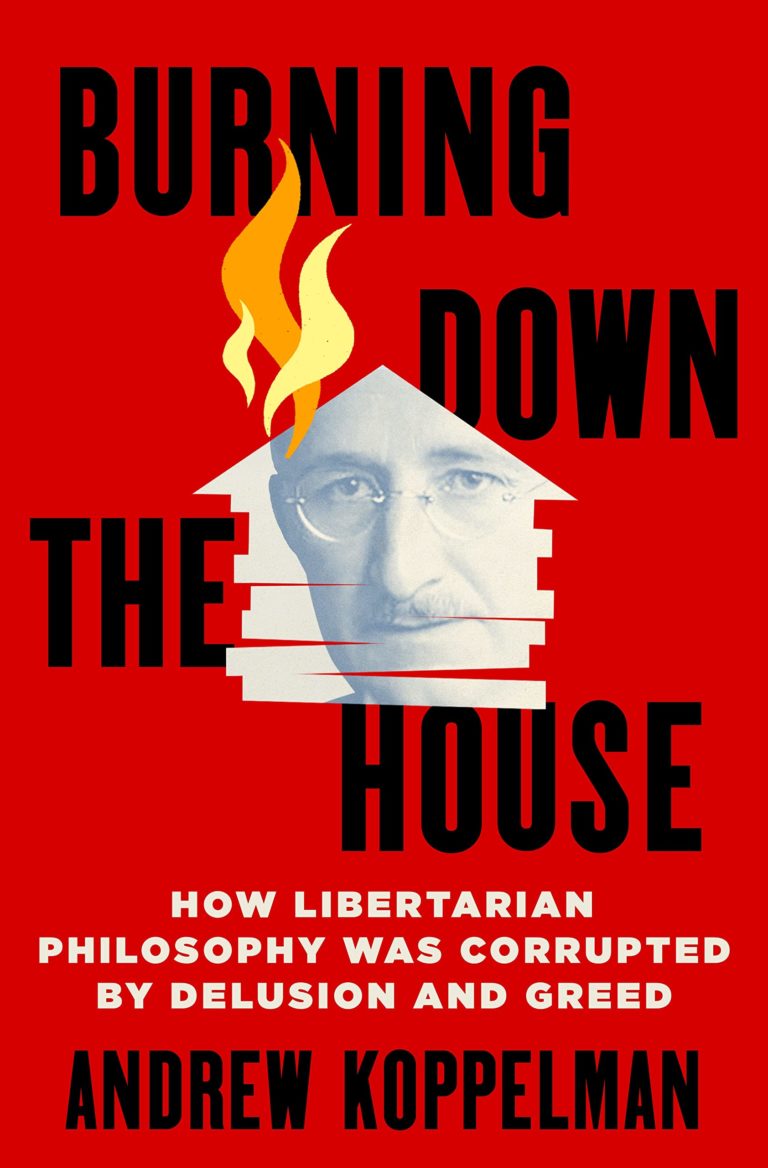

Burning Down the House

In its original, Hayekian form, libertarianism defended free markets because they promised a growing standard of living for everyone. Government should intervene only if markets fail to deliver. Regulation is necessary to prevent businesses from hurting people. Social insurance prevents destitution and gives everyone a stake in the system. The state should not, however, try to manage the economy. Originally an idea of the right, this vision now dominates the American Democratic Party.

The label of “libertarianism,” however, has been appropriated by a different view. It is hostile to anything government does: environmental regulation, Social Security, publicly funded roads and bridges. This is an undeniable issue; it endangers humanity and threatens to turn America into an oppressive plutocracy in the name of liberty.

Why did you write this book?

I became interested in libertarianism by accident. In 2010 I was invited to give a presentation about recent constitutional challenges to Obamacare. I teach constitutional law, but I hadn’t followed that litigation. So I prepared by reading the two district court cases that had recently declared part of the law unconstitutional.

I got upset. The reasoning was so flagrantly bad, so manifestly driven by the judges’ political views, that I was shocked to see such stuff coming out of the federal district courts. More such decisions followed. With only a few exceptions, judges appointed by Republicans accepted arguments that were inconsistent with nearly two hundred years of settled law.

I eventually became persuaded that the judges were in the grip of a philosophy that was no part of the Constitution, but which they found so compelling that they felt sure it had to be in there somewhere. It rested on a weird understanding of liberty, which conjured up a right previously unheard of: the right not to be compelled to pay for an unwanted service. If people wanted to go without insurance, it was tyrannical for the state to force it upon them. Government, however, provides myriad services, paid for by taxes without asking whether the recipients want them. The proposed “right” repudiated sources of economic security that most Americans depend on, notably Social Security and Medicare. More broadly, the implication was anarchy. Why should anyone believe there was such a right?

As I learned more about the origins of this litigation – a story I eventually told in my book, The Tough Luck Constitution and the Assault on Health Care Reform – it became clear to me that its deepest source was libertarian political philosophy. There were two fundamental objections to Obamacare. One was that it expanded the size of government. The other was that, while it concededly provided health care to millions who were doing without, it did so by raising taxes on prosperous people who had not themselves done anything wrong.

I thought both objections repellent. How could people believe them?

In trying to understand libertarian philosophy, I was frustrated to find that there was no general introduction to it that was not written by uncritical enthusiasts. I eventually learned that it comes in flavors, some more bitter than others. The story I learned was one of an admirable movement that became corrupted – a major part of the story of modern American politics that, weirdly, no one had told. I resolved to tell it.

In your latest book “Burning Down The House”, you have written a book of political philosophy for a general audience. Why should they care? Why is political philosophy relevant?

Political philosophy sounds abstract, but it is inescapable. If you have any political opinions, then you have a philosophy and are acting in accordance with it. Politics is not merely the pursuit of interests. Ideology matters. For example, Charles Koch, who has been funding libertarian causes for half a century, is often depicted as a greedy man hoping only to line his own pockets. This is a massive misunderstanding. Koch is an idealist. (Whether his actions have been consistent with his ideals is another matter.) To understand and critique him, it is necessary to understand the creed to which he is committed. Similarly with former House Speaker Paul Ryan’s efforts to privatize Social Security, or the antiregulatory efforts of Donald Trump.

In my last chapter, I focus on the political influence of America’s most powerful libertarian, Charles Koch. His intervention nearly crushed the Obamacare law, and he has played an immense role in hamstringing the effort to slow climate change. Libertarianism, of which he has been the most effective advocate, endangers the human race.